Mortality

On Thursday, our former neighbour died.

Manolo ‘El Minero’ was an irascible chap with a chequered history in the village. The day we arrived in Moclín, having completed our purchase of Casa Higueras, Manolo was playing Flamenco music very loudly from speakers he had installed beneath his pergola at the front of the house. He was not in good health even then, some 6 years ago, as he had been a miner in Potassium mines and this had taken a significant toll on his lungs. Despite this, he took great pride in creating a display of plants, pots and antique agricultural equipment outside his rented, ramshackle house next door to ours. The display was such that Calle Amargura, our street, was on the village map as being a ‘picturesque corner’.

As his illness progressed, he increasingly saw the negative side of life. When asked how he was, he would invariably declare himself already dead and in the last couple of years he was never seen without his oxygen mask.

Last year, he had to move from the home he had rented for 20 years as part of the roof collapsed, rendering the house uninhabitable. He left, moving to another property in the village taking his plant pots with him, seemingly regardless of whether or not the pots actually belonged to him!

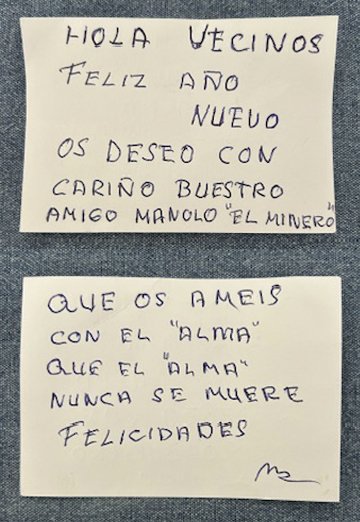

The note given to us from Manolo. New Year 2019.

When we first arrived, we had a good relationship with Manolo and exchanged gifts at Christmas. Often, these gifts came from Manolo’s kitchen but now, having seen the state of his kitchen, it is a wonder that we have lived to tell this tale. Latterly, Manolo was often angry, frustrated by life and his illness, and his neighbours bore the brunt of his frequent outbursts.

Regardless of his history, Manolo was still a neighbour of the village and his death reminds us all of the perilous state of villages like Moclín. This year, I believe that 6 (it may be more) villagers have died; some had reached very respectable ages and others died before their time but all of them represent a great loss: to other members of the family, to the community, to the longevity of the village.

At the beginning of last year, we were mentioned in an article in The Telegraph in which initiatives for stemming the tide of rural depopulation were discussed. When you consider that 6 deaths in a village where the population numbers only 200, the figures are sobering: 3% of the population has just disappeared, unlikely to be replaced. Many villages in rural Spain are clinging onto survival. There is little or no work for young people, so they have to leave to find employment in the larger towns and cities, or abroad. Although this younger generation return to their family villages frequently, it is unlikely that their own families will end up being born and brought up here, without the safety net of employment. At the other end of the line, the older generations are dying and there are very few people who are able to move into these villages to fuel the community. I recall seeing a photo of Moclín from around 1940. One of our neighbours commented that it was sobering to note that in that photo there were fewer houses but the population of the village numbered some 1,000 inhabitants. Now, there are more buildings in the village but the population is only one-fifth of the 1940’s head-count. It is easy to see that, within one generation, the village could be so under-populated that it becomes unviable.

There is now a drive to use sustainable tourism as a catalyst to transform these communities. Tourism alone, like many businesses, wouldn’t be sufficient but when you combine tourism with other commercial enterprises then the narrative can change. Moclín sits on the Camino de Mozárabe, which is part of the Camino de Santiago. As a result, there is a steady flow of hikers who pass through the village on their journey. However, a pilgrim doing a camino is not going to boost significantly the local economy. Invariably, a hiker will stay for one night in low-cost accommodation. They may go to the bar for something to eat, or buy basic provisions from the local shop, but you couldn’t plan a tourism strategy solely on the existence of walkers. To build a sustainable tourism strategy, you need to attract visitors to stay in the area for a few days, a week, a fortnight or longer. Where do you start if there is insufficient accommodation of suitable quality, or if the offering for visitors is perceived as not being enough to sustain interest or entertainment? We had a Spanish guest who stayed with us a while ago in Casa Higueras for one night; he came to walk the beautiful Ruta del Gollizno. In his review, he explained that he had a great stay and the hike was glorious, but there was nothing else to do in the area. How wrong could he be, but without providing him with the long list of everything that there is to do here, how would he know?

Investors follow the money. If there is a perception that the traffic of visitors is too low, why would an investor consider opening a new bar, a restaurant or a hotel? Business-owners are not charities, and they need to see evidence that they will get a return on any investment they might make. So, there are the two sides of the balance: convincing visitors that there is enough to do in an area to encourage them to stay and then convincing investors that there are enough visitors to make their venture worthwhile.

The article in the Telegraph was the start of an 18 month project for us that we both hope will reap huge rewards for the village. We have alluded to this project in previous posts and we still can’t reveal everything in its entirety, but we can say that it should provide enough of a stimulus across all sectors to give Moclín and the wider Province of Granada the much-needed boost to attract visitors away from the traditional and over-subscribed coastal resorts to venture inland and uncover a whole new version of Andalucia, rich in history, natural beauty, culture and wonderful, warm-hearted and generous people. With a new wave of visitors who are hungry for the unspoilt landscapes and heritage of inland Spain will come a wave of investment. Local shops will encourage artisans to sell their wares; bars will open, offering a rich variety of traditional cuisine; quality accommodation will be designed for longer stays; small businesses will spring up offering guided walks, cycling trips, olive oil harvesting and tasting, wine-tasting and destination-dining and a myriad other activities. With this growth of small businesses comes employment providing a foundation on which younger people can forge their future without the need to head to the cities. Babies are born, new generations are created, and schools reopen and with these new generations come new ideas for the future of these communities and a cycle can be restarted.

It sounds simple, but any sustainable tourism needs careful management. 100 people buying 100 houses on the back of an initiative, such as the €1 house-buying scheme, does not guarantee success - it just takes empty houses off the market. Buying a property in rural Spain comes with a responsibility: with your new home, you become a key component in the community and your local neighbours will look to you for support and encouragement, and an indication that the legacy of many, many previous generations will be in safe hands. But the return on your investment could hardly be greater.

It is an unwavering fact of life that our time will come, and we will leave this life in the hands of our families, neighbours and friends. But death shouldn’t mean the discontinuation of entire communities and the loss of everything that made those communities so rich and vibrant. Moclín, like countless other rural villages is what it is because of its history, its natural beauty and, above all, its people. Without that all-pervading spirit, without that love and that vibrancy, the village is merely a collection of buildings. In our neighbouring village of Limones, with its wonderful local mayor Lucí, there is a formidable circle of women who crochet. I’ve witnessed their beautiful creations as they labour to create bunting for the annual village fiesta, and this circle of women and their crochet could be taken as a metaphor for village life: founded on tradition and love, and pride and connection, family and community. All we need to do is pick up our crochet needles, find a seat at the table and start knitting.