Where the wild things are

On the occasional trips we have taken by bus to Madrid from Granada, we have passed through one of Spain’s gorgeous Natural Parks. Looking out of the window of the bus, we have often remarked that this is an area that we would love to explore - a vast expanse of forest and mountain that looks as wild as it is beautiful.

This area is the Parque Natural de Despeñaperros, one of Andalucia’s smallest designated natural parks. However, adjacent to this park, there are yet more spectacular areas of nature at its finest.

The Parque Natural de Despeñaperros covers a landscape created by the power of rushing water slicing and carving its way through the rocks, creating dramatic gorges, waterfalls and leaving behind a hugely rich catalogue of flora and fauna. As Andrew and I found ourselves with a few days free in the middle of September, I thought it would be the perfect time to arrange a secret trip. Doing research for the expedition revealed that there are vast tranches of Andalucia that we have yet to explore, and a visit to Despeñaperros scratches the surface of the beauty of this very northern part of Andalucia.

We allowed only two days for our little trip, staying overnight in the small town of Baños de la Encina. I had no prior idea what any of these places were like, other than the impression left by the passing glances through a bus window. However, one of the highlights that cropped up during my research was the Cascada de Cimbarra, a natural waterfall to the east of the area. This was our destination on our first day, and a relatively straightforward circular hike around the gorge and the waterfall. As soon as we got in the car, Andrew started to ask repeated questions as to where we might be headed, as I had managed to keep the secret closely guarded. After about 10 minutes of inquisition, I decided that I would have to tell him just to shut him up. That and the need for him to navigate the country roads once we left the motorway.

Despeñaperros is about 2 hours’ drive to the north of Granada, on the main Jaén to Madrid Motorway. It is the eastern-most area of a large mass of wild landscape that includes the Sierra Morena, the vast Parque Natural de la Sierra de Andújar and the Parque Natural Sierra de Cardeña and Montoro to the west, all running along the border between Andalucia and Castilla-la Mancha. Whilst we appreciate that any forested areas need maintenance to preserve the ecosystem as much as possible, this is an area of the wildest beauty where nature is very much in charge and human visitors are in the minority and fairly insignificant. Even the marked hiking routes skirt the edges of the largely untouched central expanses of this landscape. Walking through this incredible region feels like a privilege; that you are encroaching on a secret that needs to be kept and where modern day life has no place.

The drive off the motorway to Cimbarra is, as one would expect, beautiful. Interestingly, there are absolutely no signs for the waterfall, despite this being one of the highlights of this geologically breathtaking region. Thank goodness, we say. We barely passed another car on the route. Admittedly, we went on 19th September, and this area all but closes down on 15th September. The only sign we came across was on our arrival in the village of Aldeaquemada, which from first glimpse seemed to be rather unpromising. The sign to Cimbarra took us away from the heart of the village and out on a dirt track back up into the mountains. After a short distance, we came to a small parking area occupied by only one other vehicle, and that van left as we pulled up, so we had the place to ourselves. A map showed the route: a fairly easy circular trot that promised to take only 30 minutes or so. As it happened, the walk is so beautiful that, with pauses to take in the views, it fills an hour at least.

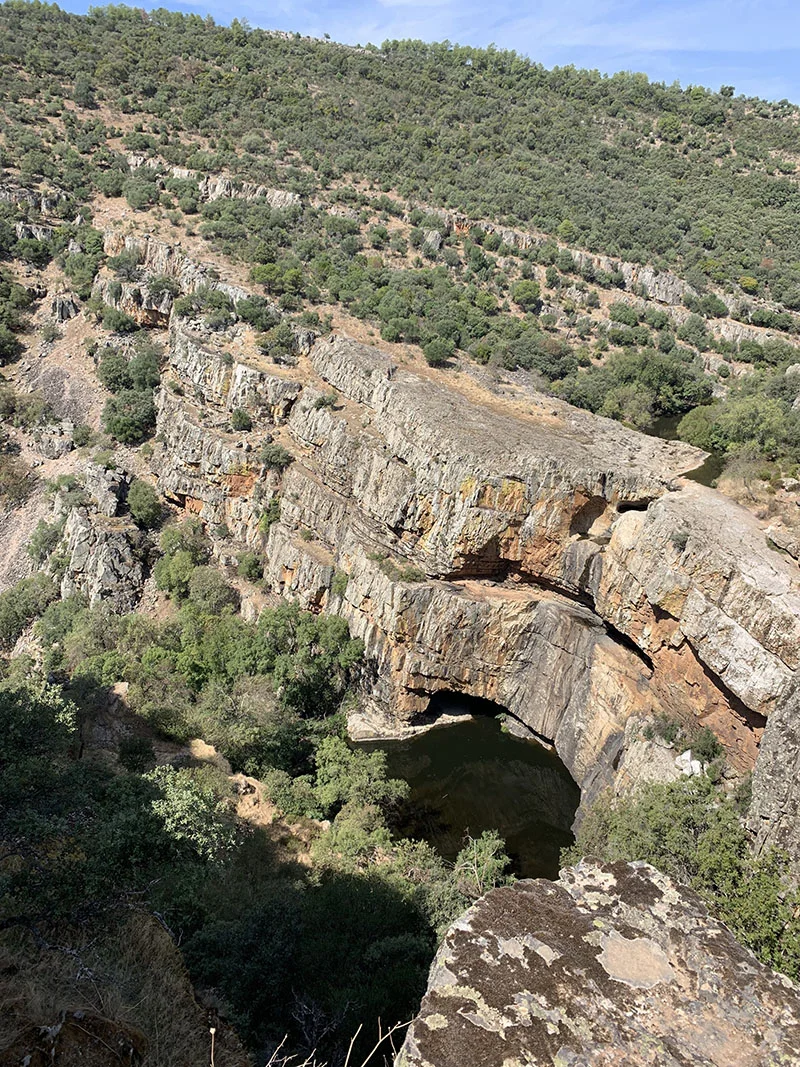

As this was September, the rivers feeding into the waterfall were probably at their lowest levels, so the waterfall was not flowing. However, the gorge is no less spectacular, and as with so much of Spain’s stunning countryside, it is almost impossible to appreciate scale and drama until you are physically right on top of, or inside the particular geological feature. It is easy to imagine how thrilling it must be when the waterfall is tumbling down into the gorge, and it is equally mind-boggling to imagine the power of water needed to cut out the majestic gorge, revealing strati of Armorican quartzite that has resisted erosion from sea and river going back 500 million years.

Standing on the plateau above the waterfall, with panoramic views and vertical drops over plunging cliffs is a humbling experience, and is, for us, one of the reasons we love Spain so much. It is a truly magnificent country.

The area abounds with reminders of the past, including examples of prehistoric art so valuable that they have been declared UNESCO Heritage sites. You could spend a week here and still only get a tiny glimpse of the extraordinary.

For lunch, we returned to Aldeaquemada and almost stumbled upon the main square which happens to be a thing of great beauty! The municipal buildings and the church have been very sympathetically restored and border this large open space, almost completely unseen from the modest road that runs alongside. We had a couple of beers and very pleasant tapas whilst watching groups of locals enjoying their respective lunches. This was village life at its best: on one table, there were probably ten men of the parish, and one woman, working their way steadily through a goodly number of bottles of local wine, and plates of very tasty-looking food. On another table, four older gentlemen sat happily chewing the cud over their own glasses of local wines. One of the chaps had bought a bag of huge local tomatoes, proceeded to slice and cut a couple with a tiny pen-knife, and set the slices out on a plate for his colleagues to enjoy. We could quite easily have been in another time, but there was no doubting that we were in rural Spain.

We spent the night in the Hotel Palacio Guzmanes, in the centre of Baños de la Encina. It is difficult to find villages in the natural parks; they just don’t seem to exist in this wilderness of mountain and forest, and Baños, as it used to be known, is 30 minutes’ drive to the south. Again, we knew nothing about the place, apart from its geographical proximity to the mountains we wanted to explore, but it is quite a charming place. The small town also must have one of the best-kept historic secrets of any place in Europe. On the edge of the village sits the Castillo de Bury Al-Hammam or Burgalimar Castle, one of the oldest fortresses in the whole of Europe. Interestingly, it is one of only two castles in Europe (the other is the Castle of Florence) that is allowed to fly the EU flag.

The construction of the castle was begun in 968, and it remains in superb condition - an oval design with walls running between 14 square towers all of the same height. The Christians added an additional tower in the 14th and 15th Centuries. The bulk of the fortress was, we discovered, built using blocks made in-situ from red sand, sea pebbles, lime to bind it all together and water. This mix was poured into wooden formwork that also provided expansion joints as the timber rotted away. Quite staggering construction technology, and remarkable that it remains standing over 1000 years later.

The day we stayed in Baños de la Encina happened to coincide with the Dia de San Mateo, to whom the village church is dedicated, and the evening saw a procession in honour of Ntra. Patrona la Virgen de la Encina. After dinner, we followed the icon as she was paraded through the streets accompanied by a rather good band, all set against a backdrop of the illuminated castle and church.

Baños de la Encina sits on the southern fringes of the Sierra Morena, one of the largest habitats for the endangered Iberian Lynx, and this is one of the reasons we will be returning for a longer stay before too long.

We had a job deciding what we should do on our second day, as it didn’t take us long to realise there was far too much to see in one visit. We decided to stay in the Despeñaperros park and save the other areas for a separate sojourn. After breakfast in our rustic little hotel, we headed for a visitor centre on the edge of Santa Elena, the northern-most village in Jaén Province. The village sits on a hill overlooking the site of one of Spain’s most important battles between the Christians and the Moors. The Batalla de las Navas de Tolosa took place on 16th July 1212 and the Christian victory marked a key moment in the ‘reconquest’ of Spain. Rumour has it that a local shepherd lead the Christian forces through hidden routes between the Sierra Morena, giving them the advantage of surprise over the 200,000-strong Moorish contingent. The Christians suffered relatively few casualties whereas the Moors suffered losses of a reported 100,000.

The guide in the visitor centre highlighted a new hiking route, the Castañar de Valdeazores which joins up with the Arroyo de Valdeazores to create a beautiful circular route of around 6.5 kms.

This proved to be a magical walk, following the river bed and ascending steadily up into the mountains. Almost as soon as we left the car behind, we found ourselves in forest made up of oak and cork for as far as the eye can see. Deep in the forest on the other side of the river, we could hear stags calling to each other, throaty sounds echoing eerily around the gorges and crags reminding us that we were the only humans here, surrounded by the wildlife that commands these hills. Through the slender trunks of trees, we would occasionally see the slender legs of a deer, peering at us through dense shrubs. This is a landscape populated by wild boar, deer, mouflon, lynx. It is also worth remembering that the Sierra Morena is home to endangered wolves.

Some parts were quite steep!

The route through the forest was very well marked and quite, quite beautiful. There were no sounds apart from the sounds of nature, but more often than not we were alone with the sound of our boots on rugged terrain and our walking poles tapping alongside. We contemplated how tragic it was that there are now so few areas of the UK that could be classified as truly wild, where endangered species could be released to forge their own existence outside captivity. So much forestry has disappeared to make way for farmland or the spread of urbanisation. It is wholly enriching to find yourself in a place where you are reminded how utterly tiny we are in the scheme of things, and how insignificant have been the past 2,000 years of our ‘modern’ history compared to the millions and millions of years that extend beyond that.

At the end of the walk, we had lunch sitting on a terrace of a restaurant looking into the gorge. Jagged quartzite fingers stand like sentries, guarding the way into Andalucia, much as they did as Christian troops were filed through fissures in the rocks to rout the Moorish armies back in 1212. And much as they have done for millions of years since massive plates collided pushing the earth’s crust upwards to form the surrounding mountains that subsequently got shaped by sea and river erosion. Over the forest, we saw upwards of 16 vultures wheeling on the thermals, their wings barely moving as they allowed the currents and flows to guide them over their domain. Earlier on our walk, we witnessed a Spanish Imperial Eagle, sunlight reflecting off its wings as it surveyed the thick forest below. One would like to think that this is an eco-system untouched by human hands, but I am sure that humans have a part to play in this evolution. Fragile eco-systems need to be managed, but these vast areas of Andalucia are reminders of the stunning beauty of nature in its raw state.

For more information about Parque Natural Despeñaperros